You are here: Home > British Military > Ordnance

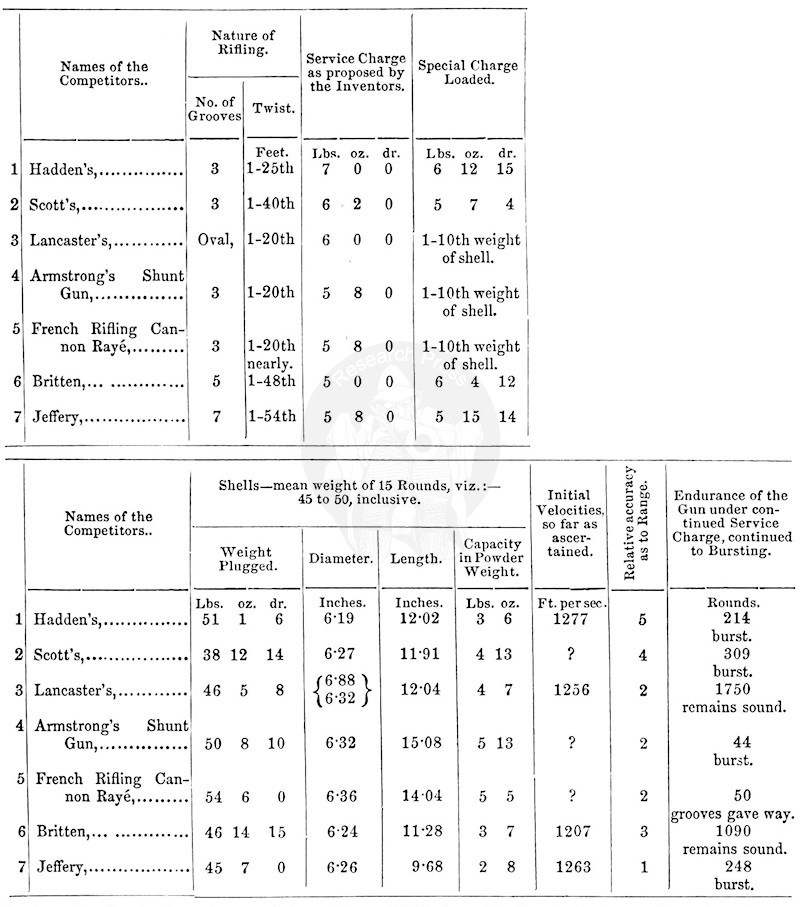

We give in Table 1 the results of the competitive trials of last year at Shoeburyness, to which we have already referred, as the most condensed form in which we can convey a certain amount of knowledge of this subject within our space.

TABLE 1 – COMPETITIVE TRAILS, RIFLED GUNS, 1861

Note. – All these guns were of cast-ron, all of 58 cwt., and bored to the 32 pounder smooth-bore calibre = 6.375 inches.

The French spiral was an increasing twist, from 0 ot 4.65 inches in 88.55 inches length

Amongst the results of these trials were these – The Hadden (1), Scott’s (2), and the French gun (5), rapidly gave way, by the grooves being unable to resist the work impressed in giving the twist; and, after a time, the bores were reduced to irregular sorts of round-sided triangles, with the angles replaced by curves.

Much metal was planed away from the grooves of the shunt gun (4). Jeffery’s gun, with the shallowest grooves and largest number – the shot being also loaded with a cloth patch, to centre it better – gave the best practice; and the Britten and Lancaster guns showed the most endurance. The continuous firing from these two last guns is still proceeding, and at the moment we write the Britten gun has withstood above 1100 rounds, and Lancaster’s more than 2000, and both, we believe, are still sound.

We must leave to such of our readers as may be competent, to draw their own inferences from these facts. The main results would not have been materially different had all the guns been of wrought-iron, of the most suitable hardness, in place of being of crumbly cast-iron; but those referring to the wear of the different forms of grooving would have been then much more instructive.

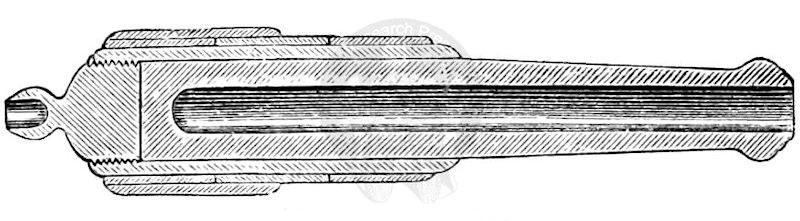

Lancaster has recently (February, 1862, No. 284) patented an improved method of strengthening cast-iron ordnance, by externally hooping, in a way proposed to add also to the longitudinal strength of the cast-iron internal piece, of which Fig. 630 is a longitudinal section.

Fig. 630: Lancaster Gun – Strengthened Cast-iron Core – Longitudinal Section

We do not believe that the cast guns of the old patterns, and one calibre or more thick, when turned down and hooped externally, have failed from want of longitudinal strength; for at such a thickness it may be proved that the tendency to burst is four times as great as that to tear across by the longitudinal strain (see Mallet on “Artillery,” &c., par. 285, p. 151), and we certainly agree with Sir William Armstrong as to the inexpediency of trying to bolster up the old smooth bores in stock and convert them into rifles – first, because the smooth bores will yet be wanted, whenever actual war shall have proved that rifled cannon have their defects as well as their advantages, and are not fit for everything; next, because no cast-iron rifled cannon, unless perhaps the oval bore, can be made, whose grooves will not crumble and be blown away within a few dozen rounds. The competitive results above given are conclusive as to this point, and hence equally so as to the utter worthlessness of cheap rifled cannon, in which a preference, on scientific grounds, is alleged to be given to cast-iron interiors; as, for example, in the 8½-inch gun of cast-iron with a steel jacket cast upon it, exhibited (2514), and called a 200-pounder, which if not burst, would have the whole of its three grooves crumbled into irregular ruts, by shot of such a weight, with proportionate charges, within 50 rounds. The grooving is Scott’s, to which this actually happened, as we have seen, with a gun of far less calibre, and throwing a shell of about one-fourth of this weight.

It is one thing to produce a huge gun that looks terrible to the ignorant and seems very cheap, quite another to provide one reliable and durable in service. The difference is the old one between the razors to sell and the razors to cut; and this difference, we have reason to believe, the Confederates have already learned as to some such guns supplied them from this country.