You are here: Home > Firearms > Long Range Target Rifles

Following defeat of the British rifle team by American riflemen at Creedmoor, USA, in September 1877, there was debate about the reasons for defeat and this discussion included talk of the rifles used.

One British enquirer wrote to the Volunteer Service Gazette seeking information on Remington and the Sharps Creedmoor rifles. He was rewarded with a detailed reply from Irish gunmaker, John Rigby, a member of the Irish team to Creedmoor in 1874 and maker of the famous Rigby muzzle-loading match rifles used by the team. Both the original letter and John Rigby’s reply are reproduced below.

It’s interesting comment on the American rifles by a well known Irish gunmaker and touches on another wider debate, that of the development of purely target rifles, and the practical application of the advances (i.e for military use).

THE AMERICAN RIFLES

TO THE EDITOR OF THE VOLUNTEER SERVICE GAZETTE

Sir, – Will you allow me, through the medium of your journal, to ask some of the gentlemen who are familiar with the Remington and the Sharp Creedmoor rifles, if they will favour your readers with an accurate description of these weapons. I have no doubt there are many of your readers who, like myself, take a great interest in small-bore shooting, that have but a very imperfect idea of the peculiar characteristics of these arms, and by such persons reliable information as to the weight and length of barrel, calibre, number, and description of grooves, breech mechanism, methods of loading, &c., would certainly be read with interest, and would assist one in following up the very important discussion now going on in your columns. My request may seem an unnecessary one to those who, living near the city, have constant opportunities of seeing the latest improvements in small-bores, but I can assure you that it is a hard task to get at the facts in such matters when living at distance from those centres where small-bore most do congregate. – Yours faithfully,

“Martini.”

Source: Volunteer Service Gazette, Saturday 3 November 1877

THE AMERICAN RIFLES

TO THE EDITOR OF THE VOLUNTEER SERVICE GAZETTE.

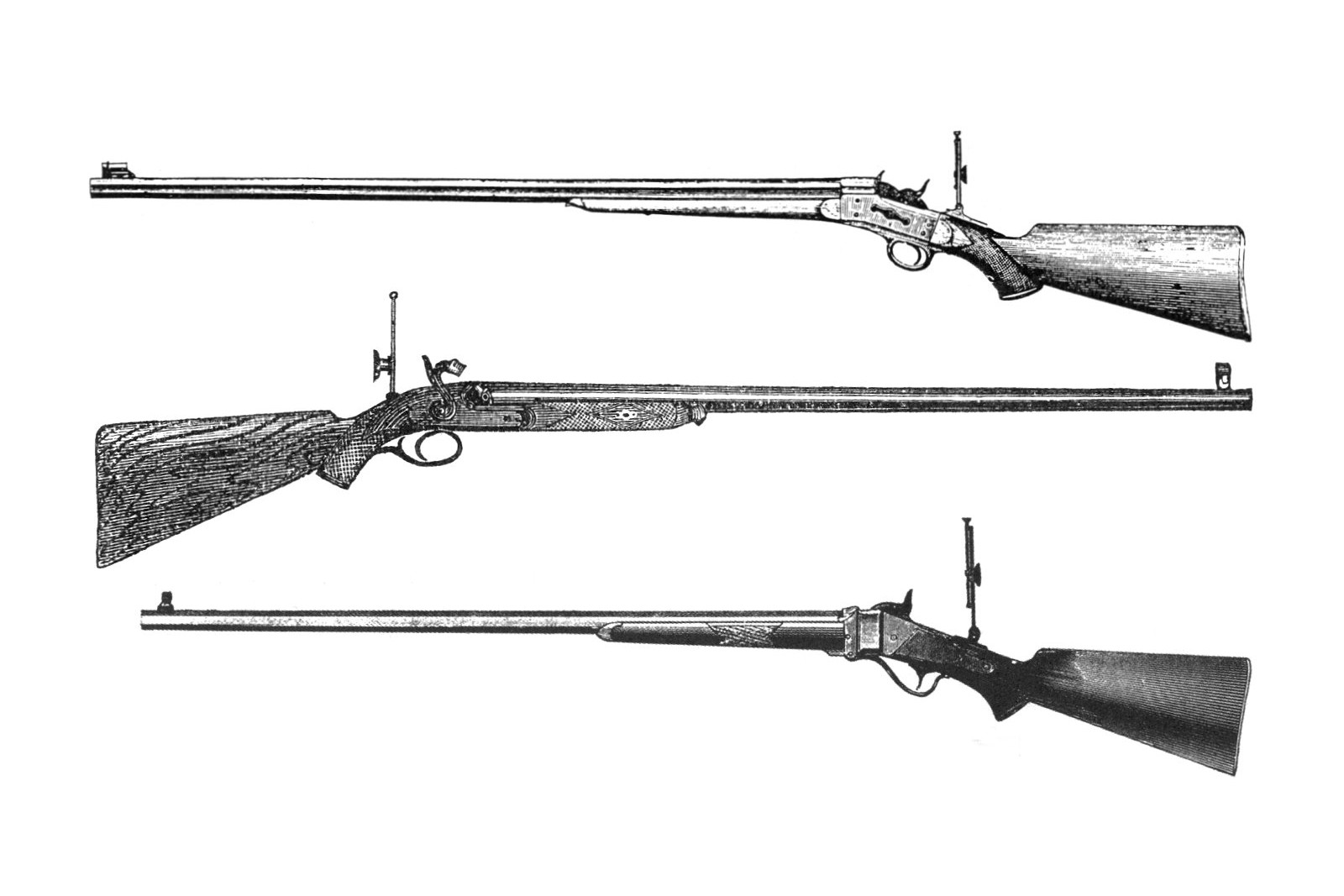

Sir, – In reply to Martini’s inquiry as to American rifles, I can give him the information he seeks, as I have had and used both Remington’s and Sharp’s rifles since 1874, and several of my countrymen procured in 1875 Remington Creedmoor rifles, moved thereto by the fine scores of their American visitors in that year. As the breech action is difficult to describe without drawings, I will pass it over, merely remarking that in both systems a clear view can be had through the barrel, and there is every facility for cleaning from the breech. In both the cocking is effected with the thumb before opening the breech. The form of gun, weight and length of barrel, resemble generally the Match rifle used in England. The system of sights, spirit-level, and windgauge is likewise similar to ours, differing only in minor details. The back-sight is generally used on the handle of the stock, and not on the butt; but there is much difference of opinion on this point, as one-half of the American Team of this year used it in the latter way. Accustomed to good light, the necessity which often exists, in our climate, of getting the eye close to the back aperture in order to see plainly, does not influence the American in his choice of position. And this one advantage of the forward over the back position, which in bad light counterbalances all its defects, is lost in the transparent atmosphere and with the sunlit targets of Creedmoor.

The barrel of the Remington is very slightly smaller in bore than the Martini. The rifling is five shallow grooves, of width equal to the spaces left between them. The pitch of spiral (one turn in eighteen inches) is equal from end to end. The bullet is 550 grains weight, similar in shape to the Metford, but hitherto rather blunter or fuller in the head. It is longer than either Metford’s or my bullet, and about the same degree of hardness as that of the Government Martini. The paper used is very thin bank-note paper. The barrel is chambered to fit closely a drawn brass case, which holds, when filled quite up, about 95 grains of powder. The charge for the Remington is, however, but 90 grains, and the latest Sharp cartridge will hardly hold more even when shaken down: 90 grains of American powder is equal in strength to about 75 grains of Curtis and Harvey’s No. 5 or 6. It is slow burning, depositing a good deal of fouling, and is most nearly approached in English powders by some of the cheaper brands, sometimes called Volunteer powder, and such-like. The correct performance of the American breech-loader seems to depend a great deal on the use of this particular kind of powder. Curtis and Harvey’s No. 6 does not give good shooting, upsetting the bullet too much and leading the barrel. We now come to the distinctive feature which forms the strength and weakness of the American system. It was originated by the Remington Company, and adopted lately by all others. No provision is made for effects of fouling; no wad or lubricant to obviate such effects is used. The cartridge-case is filled up with powder, room only being left to insert the base of bullet for about one-tenth of an inch. The cartridge so loaded cannot be carried in packages or ordinary pouches; each must be supported in its compartment so that the bullet cannot become displaced, and must be most carefully handled in conveying it into the chamber, otherwise the bullet will fall out and the powder escape. This system presupposes the perfect cleanliness of the barrel. If the least particle of fouling were left adherent in front of the chamber, the bullet would not enter; and if forced, the paper envelope would be torn.

Not only must the barrel be clean, but it must be in the same state each time as regards lubrication; and this is effected by the adoption of a systematic method of cleaning. Each man carries a number of cleaning-rods (generally four), little bottle with water, and another with oil, and a good supply of cotton patches for the cleaning-rods. After each shot, a wet or damp brush is passed through; then a dry cotton patch to clean and dry the surface; thirdly, a patch with oil; and lastly, a clean one to remove the superfluous oil. It is also usual to oil slightly the outer paper of the bullet, but this is done very sparingly.

I have said that this feature forms the strength and weakness of the American system. The strength, because when carefully carried out it frees the rifle from the influence of heat, cold, dryness, or damp. The friction experienced by the projectile in passing through the barrel is absolutely independent of the quality of powder, and of all those circumstances which, where no cleaning is used, and in a breech-loader especially, powerfully influence the result. The weakness, because it deprives the system of practical application. A Creedmoor rifle cannot be used with even moderate accuracy unless so cleaned. A second cartridge, with the full charge, cannot be even inserted uninjured unless the fouling of the previous shot is removed. It is the reproach of the British Match rifle that it is obsolete as a weapon of war. The Creedmoor rifle is open to the same objection. It is a breech-loader that cannot be loaded at the breech without the aid of cleaning-rods; and the accuracy so attained is even less available for practical uses than that of the muzzle-loader, which, under ordinary circumstances, can be fired all day uncleaned without serious loss of accuracy.

It may fairly be suggested here that, by modifying the cartridge, it would be possible to use the Creedmoor rifle as a breech-loader proper; but when this is done, it by no means follows that it will be found as efficient in its new character of a military breech-loader as it has proved itself to be when specially loaded and cleaned.

If in the descriptive particulars I have given there are omissions, the reluctance to occupy more of your space must be my excuse; but I shall be happy to answer any inquiries made to me directly by those who may desire further information. The price of a good Creedmoor rifle and sight is from 20l. to 25l. sterling. – I am, &c,

John Rigby

Dublin, Nov. 7, 1877

Source: Volunteer Service Gazette, Saturday 17 November 1877