You are here: Home > Research > Hex Bore

Written by: David Minshall

Introduction > Target Shooting > Dominance Wanes

During the 1850s and 1860s the British service rifle calibre was .577, both for the muzzle-loading Enfield rifle and its breech-loading successor the Snider (a conversion of the Enfield). Early manufacture of the Enfield relied on much hand labour and consequently lead to problems of inconsistent performance, non-interchangeability of parts and slow supply. Joseph Whitworth was approached to provide assistance with regards to the design of appropriate machinery for its manufacture.

Joseph Whitworth was the foremost manufacturer of machine tools of his time. Not content with considering the machinery for the manufacture of the rifle, he determined that a more appropriate course of action would be to establish that the proposed rifle was of optimum design before considering its mass production. In Whitworth’s 1873 book, ‘Guns and Steel’, he writes:

“IN the year 1854, when Lord Hardinge (the then Commander-in-Chief) was endeavouring to obtain the best possible rifle with which to arm the British troops, he requested me to aid him by investigating the mechanical principles applicable in the construction of an efficient weapon. I willingly agreed to do so, subject, however, to the condition that I should have a suitable gallery, protected from changes in the wind and from fluctuations in the atmosphere, wherein to carry on the experiments which were necessary for enabling me to arrive at any sound conclusion.

“It was absolutely essential to track the path of a rifle bullet throughout its entire course, to determine whether its point preserved a true forward direction, and to record its trajectory. This could be done most readily in a closed gallery provided with screens of very light tissue paper.

“Accordingly a gallery, 500 yards in length, was erected in my grounds at Rusholme (Manchester), in the year 1855. Its height was 20 feet and width 16 feet; it was slated, and had openings on the south side only for the admission of light and for getting rid of the smoke.”

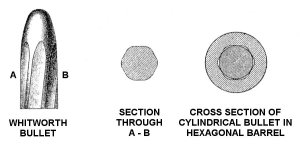

The only design criteria Whitworth had was restriction to the service charge of 70 grains with a 530 grain weight bullet. The conclusion of his experiments was that the optimum bore for the charge and weight bullet specified would be .45 cal with a 1 in 20” twist to the rifling. Figures relating to the Enfield and Whitworth rifles are shown in the table below.

| Bore dia | Bullet Weight | Bullet Length | Rifling | |

| Enfield (P.53) | .577 | 530 grains | 1.81 diameters of the bore | 1 in 72″ twist |

| Whitworth | .45 | 530 grains | 3 diameters of the bore | 1 in 20″ twist |

Whitworth’s rifling was a radical departure from that used on the current service rifles, being of hexagonal form and shooting a mechanically fitting bullet (see figure at right). It should be noted that the polygonal rifling was not an original idea, having been previously considered by that great engineer, Brunel.

Despite rifle trials which resulted in Whitworth’s favour his rifle design was never adopted, and the large bore service rifle continued in use until the Snider was replaced by the .45 calibre Martini-Henry in 1871. Whitworth somewhat acrimoniously summed up the development of the rifle in his ‘Guns and Steel’:

“The superiority of the Whitworth, as compared with the Enfield rifle, was first proved in a series of trials made at Hythe, in the year 1857, under the direction of Lord Panmure, then Minister of War.

“These trials led to no satisfactory conclusion, and after a lapse of eighteen months a Committee of Officers reported to the Government in 1859 that the bore of my rifle was too small for use as a military weapon.

“Compare with this the report of another Committee of Officers made in 1862, “that the makers of every small-bore rifle, having any pretensions to special accuracy, have copied to the letter the three main elements of success adopted by Mr. Whitworth, viz., diameter of bore, degree of spiral, and large proportion of rifling surface.”

“In 1869 a Special Committee reported to the War Office that the calibre of a breech-loading rifle, should be .45 inches, as appearing to be the most suitable for a military arm. This conclusion is directly contrary to that arrived at in 1859, but is the exact bore which I recommended in 1857.”

While Whitworth may have missed out on a lucrative military contract, other events in the UK were to create a new market for his rifles.