You are here: Home > Firearms > British Military Longarms > Lee Magazine Rifles

Written by: W.W. Kimball, U.S.N., U.S. Inspector of Ordnance

England has lately adopted a small-bore – 0.303 inch calibre – modified Lee magazine rifle – a Lee with most of the strong points of the mechanism modified out – after making a long series of most amusing steps of development in order to reach the conclusion that this arm was suited to her needs. For some years she has been more than content with her famous 0.45 inch calibre single-loading Martini-Henry rifles and Boxer cartridges – guns almost as bad in principle of breech mechanism as our own Springfields, and cartridges even worse than the United States regulation ones – and in her late “wars with peoples who wear not the trousers,” her soldiers have gallantly fired on the enemy when they knew full well what a horrible punishment they were to receive from the brutal recoil of their weapons, and have borne their torture with true English grit. An English officer informed the writer that the practice was a great aid to gallantry in battle in South Africa, for “when a fellow has been so brutally pounded by his own rifle half a hundred times, he don’t so much mind having an assegai as big as a shovel stuck through him; it’s rather a relief, don’t you know.”

But the idea of the small-bore magazine rifle was bound to find its way across the Channel from the Continent, and, aided by the hard work of the more advanced English military men, it slowly forged ahead to the position of adoption it now holds. The same objections to the type of arm were made in England that are now heard in the United States. The conservatives asserted that with a magazine rifle the man would fire away all his cartridges. It was explained that if the fire was made to tell, as it might, with the use of proper guns, it was not half a bad idea to fire away cartridges; that, in deed, some people thought cartridges should be fired from guns even if it soiled them with powder grime. Then it was objected that the small bullet would make only a little hole in a man, and that it was much more satisfactory to literally let daylight through one’s enemy than to puncture him in such a dilettante fashion. This is an article of good old Anglo-Saxon military faith that is hard to abandon when one has been bred in it. To-day we like the idea of putting big holes and ragged ones through our enemies, even as did that ingenious Englishman, Puckle, who, a couple of centuries ago, invented a machine cannon provided with two sets of chambers, “onne withe rounde holes for shooteynge rounde bulletes agaynst ye Chrystiannes, and ye other withe square holes for shooteynge square bulletes agaynst ye Turkes.”

The argument, which has not yet been felt in the United States, was efficiently made in England to prove that all one really needed to do in battle, in the way of hitting an enemy, was to deliver a blow of sufficient force to drop him in his tracks, and make him stop being disagreeable with his shooting, and that if one could hit him hard enough, it was just as well to do it with a fast-flying small bullet, as with a slow-going big one, while it was a much easier, surer, and simpler thing to do.

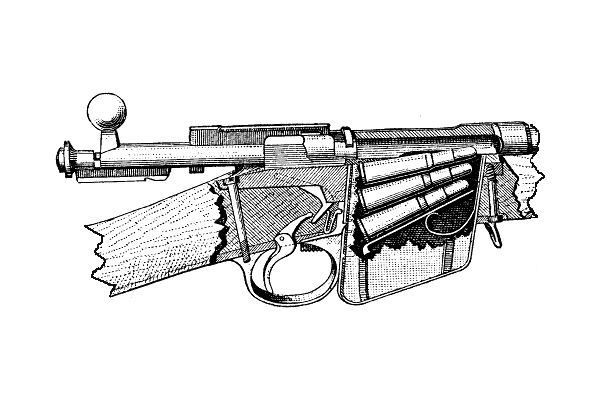

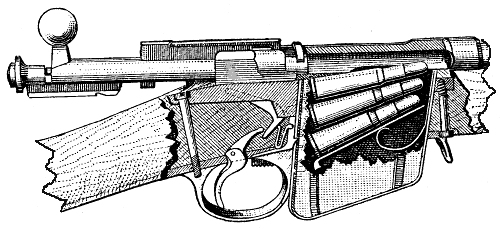

At last the Lee rifle, with its detach-able magazine, was tried, and, being found wanting, was improved backward into the Lee-Burton, an arm with a Lee bolt and a fixed under-barrel tubular magazine. But this arm was too absurd even for the conservative men who recommended it, and finally the small-bore Lee was regularly adopted. Then the conservatives had their innings. The magazine was detachable and might be lost. So it was chained to the gun, and the arm was thus prevented from having the chief merit of the system – facility for being made a true single-loader or a real magazine arm at will. The reason for chaining the gun and magazine together is excellent, but the idea is not thoroughly carried out; if it were, all the detachable parts should be chained together: the bayonet and cleaning-rod by a couple of small chains, and the cartridges by a hundred very little ones to the gun; the gun by a stouter one to the man, and the man by a good strong one to his comrades.

The magazine of the Lee system is designed to carry the cartridges one above the other, so that the spring which pushes them up can be sure to serve them to the receiver without jamming; but the system was put aside in England because it was held that not enough charges could be stowed in that way without carrying the bottom of the magazine too low down, and a curious wide affair adopted, which holds three cartridges more, by making them lie in quincunx order, and thus destroys all certainty of feed. In the magazine offered, the feed-up was so sure that by quickly reciprocating the bolt all five of the contained cartridges could be thrown out before the first had fallen to the ground; in the one adopted, the recoil from firing is needed to help the feed, and even then the only sure thing to be predicted about it is that the cartridges will jam and refuse to feed up sooner or later. The arm was designed to be used normally as a single-loader, which, in an instant, by the application of a charged magazine, could be changed to a magazine arm. By the chaining on of the magazine the British authorities have changed it to a weapon on which the magazine must always be carried, and since this last is not arranged to recharge quickly, it must in action be carried charged and cut off, so that the single-loading feature can be used for the greater part of the firing. This makes a “cut-off” nuisance necessary. Apparently the British authorities wanted the bad features of a fixed magazine, and insisted upon having them.

They have gotten them at the expense of nearly all the good points of the mechanism they have chosen, and have missed the best features of a fixed system.

Ballistically the English Lee is good, and by accentuating the fact that the guns shoot well, and that the new cartridges are excellent, while carefully avoiding the question of why there is any magazine at all, the authorities can doubtless make the brave British soldier as proud of his curious weapon as is the gallant French warrior of his old-fashioned arm, the Lebel.

Source: The Small Arms of European Armies, 1889

The full article, ‘The Small Arms of European Armies,’ is reprinted in Research Press Digest 2021.