Introduction > Rifle > Equipment > Ammunition > Shooting > Cleaning > Bedding

The Rifle

The first, and most obvious, requirement is a rifle. The original Pattern 1853 Rifle had a three grooved barrel 39 inches long with a spiral of one turn in 78 inches. It was decided that the length should remain that of the Pattern 1851 Minié and the earlier muskets, as it was thought necessary to retain the long arm with its bayonet for the Line Infantry. In order to avoid confusion with the traditionally short barrelled arms of the Rifle Regiments, the new rifle was to be designated a Rifle-Musket. This arm ran through four basic variations between 1853 and 1861, although all retained the three grooves and 78 inch twist. Huge numbers of the Pattern 1853 were made for the Government by the Enfield factory, the London Armoury Company, the English Gun Trade, and the factories of Liège, St.Etienne and in Windsor, Vermont. In addition to these well over a million (no one knows how many) were made privately for the Volunteers and for export. About half a million were purchased by the Federals in the American Civil War as well as a vast number by the Confederates.

The later arms were made to much more precise tolerances than the earlier ones and had the added advantage of progressive depth grooving. They are therefore the best for the modern shooter. The products of the London Armoury Company and the Enfield factory can usually be guaranteed to give almost certain satisfaction. Unfortunately Government owned rifles made by L.A.Co. and Enfield were very nearly all withdrawn and converted to Snider breech loaders between 1866 and 1870. However, the London Armoury Company also made, in addition to its War Office contracts, many thousands of Pattern 1853 Rifles for private sale, principally to the Volunteers. As these were not government property and yet were made to full ordnance specifications, they have not only survived well but also shoot well. As an aside, it ought to be mentioned that the story that the L.A.Co. supplied large numbers of rifles to the American Civil War has no foundation. Their production was swallowed up by the War Office and the Volunteer Movement. Parker-Hale Limited have produced an excellent reproduction of this model and other companies have also provided replica models but these do not compare with the Parker-Hale for authentic feel. Unfortunately, this Company is no more.

1853 also saw the introduction of the Artillery Carbine, also designated as a Short Rifle, which had a 24 inch barrel with the same three grooves and 78 inch spiral. Although a fine short range off-hand rifle, it cannot compare with the long rifle for accuracy. This arm had three variations. The first two (1853 and 1858) were only marginally different but the third model of 1861 had a heavier 24 inch barrel with five grooves and a spiral of 48 inches. Its sight was also made like a short version of the long rifle sight, but up to 600 yards, instead of the 300 yard leaf sights of the first two versions. This model is almost non existent in its original muzzle loading form as it was never issued and all stocks were subsequently converted to Snider breech loaders. It is mentioned as Parker-Hale produced the third model in replica form as the first of their excellent series of Enfield Rifles. There was also a 21 inch barrelled Cavalry Carbine but this is not considered as a contender for serious shooting.

The demand for shorter rifles for Rifle Corps, Volunteers and for Sergeants led to a series of 33 inch barrelled Short Rifles, the first of which was the Pattern 1856. This had a light barrel of three grooves with the same 78 inch spiral as the long rifle. Its bayonet was a heavy Yataghan Sword. It was supplemented by two other models with the same rifling which are so rare that they are unlikely to be encountered in Issue form by the average shooter. The first of these was the Pattern 1857 for Sergeants of Native Infantry, a brass mounted arm taking the same socket bayonet as the Pattern 1853. The second was the Pattern 1858 “Bar on Band” which was designed to take some of the strain of the heavy bayonet away from the light barrel by transferring the sword bar to the front barrel band. Quite a large number of arms conforming more or less to the Pattern 1856 design were privately made for the Volunteers and these are the most likely to be encountered today. With their light barrels and slow twist they do not prove to be the best for target shooting.

The shortcomings of the 1856 model led to the introduction of a heavy barrel with five groove rifling and a twist of 48 inches, the sword bar reverting to its original place on the stronger barrels. The first of these was the Pattern 1858 Naval Rifle. This is the model which has been introduced in replica form by Parker-Hale as their 1858 Naval Rifle. It is the opinion of this writer that this is certainly the best of the Parker-Hale Enfield series and is the one that the aspiring shot, who cannot find an original, should make every effort to secure. In 1861, the Army also adopted the heavy, progressive depth, five grooved barrel with its 48 inch spiral and these two models are recognised as the best for serious target shooting. Once again, both these models are extremely scarce in their original form of Government owned rifles although, as with the long rifles, a great many were privately made for the Volunteers.

The last rifle to be considered in this series is the Lancaster Oval Bored Engineers’ Short Rifle with its 31½ inch barrel to Lancaster’s unusual design. These are also very rare and hardly ever encountered on the shooting range. They have a reputation for never fouling, which the writer can confirm, but, at the same time, they are notorious for throwing sudden wild shots.

The Patterns of 1853, 1857, 1858 Naval, Artillery and Lancaster were all brass mounted and the Army Short Rifles were iron mounted.

Before turning to shooting techniques, a summary of the rifles most likely to be available for the shooter are the Volunteer Pattern 1853 Long “Three Band” Rifles, Parker-Hale’s version of the same, Short Volunteer “Two Band” Rifles in three and five groove formats with Parker-Hale’s Naval Rifle and a variety of Volunteer Rifles which do not exactly conform to any Pattern. An example of one of these is a heavy five groove Bar on Band which is perfectly acceptable on the range.

The most important consideration for all competition shooting to MLAGB, HARC, and MLAIC Rules is that the sights must conform to Issue Pattern. The writer owns a fine Volunteer version of a Pattern 1856 but with Lancaster’s Oval Bore. This is ineligible for Military Rifle competition because the front sight is an undercut bead instead of an inversed “V” although it is not ruled out by the rifling variation. When seeking an original the one to go for, if at all possible, is a Volunteer London Armoury Co. Pattern 1853. These make a great deal of money today because of their justly earned reputation on the range but their survival rate is good and they can be found, for a price, at most Arms Fairs. Although two to three times the price of a Parker-Hale, they are still worth buying, if possible, because not only will the buyer obtain a fine shooting rifle but he will also be making an excellent investment.

There is one point which should be born in mind. If your eyes are not what they were, there is a distinct advantage in going for the Short Rifle with its 33 inch barrel, rather than the Long Rifle, because the backsight is placed four inches further away from the eye. This improvement was dropped for some reason in the newly made Snider Mark III Short Rifle which placed the sight in the same position, just ahead of the breech, as the Long Enfield and Long Snider. However, the earlier converted Snider Short Rifles retained their original sights.

The final point about the rifle is that the nipple must be in good condition and original nipples should ALWAYS be changed for the modern type based on the “reversed cone” principle. These use a small hole at the bottom of the nipple with a large opening at the top. This concentrates the flash down into the charge while, at the same time, reducing the amount of back blast. Original nipples were the other way round and this allowed a great deal of flame and fouling to escape as well as causing problems with weak caps. The damage to the woodwork ahead of the nipple lump on some original rifles shows as a groove burnt quite deeply into the wood and the fouling that has been driven under the barrel at that point is often the cause of quite severe corrosion. New Enfield nipples are freely available from muzzle loading dealers and from the Muzzle Loaders Association of Great Britain. It is quite possible that an original rifle will have its nipple so firmly locked in by age and rust that it will have to be taken to a specialist gun smith to be freed. See the remarks under CLEANING for the use of PTFE Tape to prevent future problems of this nature.

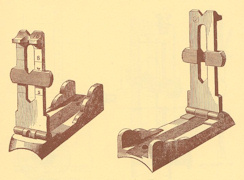

Improved “reverse cone” nipples –

(a) & (b) top and bottom views

of the improved nipple.

(c) Phosphor bronze model.

(d) Steel model with PTFE tape

on the threads.

Given a good Enfield, the practised shooter can enjoy competitive target work at all ranges out to 600 yards. At the longer ranges, wind judgement becomes very important especially given the absence any adjustment for wind on the sights.